Abstract

A sequence A of positive integers having the property that no element \(a_i \in A\) divides the sum \(a_j+a_k\) of two larger elements is said to have ‘Property P’. We construct an infinite set \(S\subset \mathbb {N}\) having Property P with counting function \(S(x)\gg \frac{\sqrt{x}}{\sqrt{\log x}(\log \log x )^2(\log \log \log x)^2}\). This improves on an example given by Erdős and Sárközy with a lower bound on the counting function of order \(\frac{\sqrt{x}}{\log x}\).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Erdős and Sárközy [9] define a monotonically increasing sequence \(A=\{a_1<a_2< \ldots \}\) of positive integers to have ‘Property P’ if \(a_i \not \mid a_j+a_k\) for \(i<j \le k\). They proved that any infinite sequence of integers with Property P has density 0. Schoen [15] showed that if an infinite sequence A has Property P and any two elements in A are coprime then the counting function \(A(x)=\sum _{a_i<x}{1}\) is bounded from above by \(A(x)<2x^{\frac{2}{3}}\) and Baier [1] improved this to \(A(x)<(3+\epsilon )x^{\frac{2}{3}}(\log x)^{-1}\) for any \(\epsilon >0\). Concerning finite sequences with Property P, Erdős and Sárközy [9] get the lower bound \(\max A(x) \ge \lfloor \frac{x}{3} \rfloor +1\) by just taking A to be the set \(A=\{x, x -1, \ldots , x - \lfloor \frac{x}{3} \rfloor \}\) for \(x \in \mathbb {N}\).

Erdős and Sárközy also thought about large sets with Property P with respect to the size of the counting function (cf. [9, p. 98]). They observed that the set \(A=\{q_i^2: q_i \text { the }i\text {-th prime with }q_i \equiv 3 \bmod 4\}\) has Property P. This uses the fact that the square of a prime \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\) has only the trivial representation \(p^2=p^2+0^2\) as the sum of two squares. With this set A they get

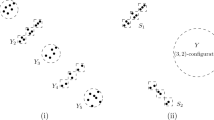

Erdős has asked repeatedly to improve this (see e.g. [6, p. 185], [7, p. 535]) and in particular, Erdős [7, 8] asked if one can do better than \(a_n \sim (2n \log n)^2\). He wanted to know if it is possible to have \(a_n < n^2\). We will not quite achieve this but we go a considerable step in this direction. First, we observe that a set of squares of integers consisting of precisely k prime factors \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\) also has Property P. As for any fixed k this would only lead to a moderate improvement, our next idea is to try to choose k increasing with x. In order to do so, we actually use a union of several sets \(S_i\) with Property P. Together, this union will have a good counting function throughout all ranges of x. However, in order to ensure that this union of sets with Property P still has Property P, we employ a third idea, namely to equip all members \(a\in S_i\) with a special indicator factor. This seems to be the first improvement going well beyond the example given by Erdős and Sárközy since 1970. Our main result will be the following theorem.

Theorem

The set \(S \subset \mathbb {N}\) constructed explicitly below has Property P and counting function

We achieve this improvement by not only considering squares of primes \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\) but products of squares of such primes. More formally we set

Here the sets \(S_i\) are defined by

where \(\nu \) is the product of exactly i distinct primes \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\) and we recall that \(q_i\) is the i-th prime in the residue class \(3 \bmod 4\). The rôle of the \(q_i\) is an ‘indicator’ which uniquely identifies the set \(S_i\) a given integer \(n \in S\) belongs to. Results from probabilistic number theory like the Theorem of Erdős-Kac suggest that for varying x different sets \(S_i\) will yield the main contribution to the counting function S(x). In particular for given \(x>0\) the main contribution comes from the sets \(S_i\) with

The study of sequences with Property P is closely related to the study of primitive sequences, i.e. sequences where no element divides any other and there is a rich literature on this topic (cf. [10, Chapter V]). Indeed a similar idea as the one described above was used by Martin and Pomerance [13] to construct a large primitive set. While Besicovitch [3] proved that there exist infinite primitive sequences with positive upper density, Erdős [4] showed that the lower density of these sequences is always 0. In his proof Erdős used the fact that for a primitive sequence of positive integers the sum \(\sum _{i=1}^{\infty }{\frac{1}{a_i\log a_i}}\) converges. In more recent work Banks and Martin [2] make some progress towards a conjecture of Erdős which states that in the case of a primitive sequence

holds. Erdős [5] studied a variant of the Property P problem, also in its multiplicative form.

2 Notation

Before we go into details concerning the proof of the Theorem we need to fix some notation. Throughout this paper \(\mathbb {P}\) denotes the set of primes and the letter p (with or without index) will always denote a prime number. We write \(\log _k\) for the k-fold iterated logarithm. The functions \(\omega \) and \(\Omega \) count, as usual, the prime divisors of a positive integer n without respectively with multiplicity. For two functions \(f,g : \mathbb {R} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) the binary relation \(f \gg g\) (and analogously \(f \ll g\)) denotes that there exists a constant \(c > 0\) such that for x sufficiently large \(f(x) \ge cg(x)\) (\(f(x) \le cg(x)\) respectively). Dependence of the implied constant on certain parameters is indicated by subscripts. The same convention is used for the Landau symbol \(\mathcal {O}\) where \(f=\mathcal {O}(g)\) is equivalent to \(f \ll g\). We write \(f=o(g)\) if \(\lim _{x\rightarrow \infty } \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=0\).

3 The set S has Property P

In this section we verify that any union of sets \(S_i\) defined in (2) has Property P.

Lemma 1

Let \(n_1,n_2\) and \(n_3\) be positive integers. If there exists a prime \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\) with \(p | n_1\) and \(p \not \mid \gcd (n_2,n_3)\), then

Proof

We prove the Lemma by contradiction. Suppose that \(n_1^2|n_2^2+n_3^2\). By our assumption there exists a prime \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\) such that \(p|n_1\) and \(p \not \mid \gcd (n_2,n_3)\). Hence, w.l.o.g. \(p \not \mid n_2\). We have

and since p does not divide \(n_2\), we get that \(n_2\) is invertible \(\bmod \) p. Hence

a contradiction since \(-1\) is a quadratic non-residue \(\bmod \) p. \(\square \)

Lemma 2

Any union of sets \(S_i\) defined in (2) has Property P.

Proof

Suppose by contradiction that there exist \(a_i \in S_i\), \(a_j\in S_j\) and \(a_k \in S_k\) with \(a_i<a_j \le a_k\) and \(a_i|a_j+a_k\). First suppose that either \(S_i \ne S_j\) or \(S_i \ne S_k\). Define \(l \in \{0,2\}\) to be the largest exponent such that \(q_i^l|\gcd (a_i,a_j,a_k)\) where we again recall that \(q_i\) was defined as the i-th prime in the residue class \(3 \bmod 4\). Then

By construction of the sets \(S_i,S_j\) and \(S_k\) we have that \(q_i\big |\frac{a_i}{q_i^l}\) and w.l.o.g. \(q_i \not \mid \frac{a_j}{q_i^l}\). An application of Lemma 1 finishes this case.

If \(S_i=S_j=S_k\) then \(\Omega (a_i)=\Omega (a_j)=\Omega (a_k)\). If there is some prime p with \(p|\frac{a_i}{q_i^4}\) and (\(p\not \mid \frac{a_j}{q_i^4}\) or \(p \not \mid \frac{a_k}{q_i^4}\)) we may again use Lemma 1. If no such p exists, then \(a_i|a_j\) and \(a_i|a_k\) trivially holds. With the restriction on the number of prime factors we get that \(a_i=a_j=a_k\). \(\square \)

4 Products of k distinct primes

In order to establish a lower bound for the counting functions of the sets \(S_i\) in (2) we need to count square-free integers containing exactly k distinct prime factors \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\), but no others, where \(k \in \mathbb {N}\) is fixed. For \(k \ge 2\) and \(\pi _k(x):=\#\{n \le x: \omega (n)=\Omega (n)=k\}\) Landau [11] proved the following asymptotic formula:

We will need a lower bound of similar asymptotic growth as the formula above for the quantity

Very recently Meng [14] used tools from analytic number theory to prove a generalization of this result to square-free integers having k prime factors in prescribed residue classes. The following is contained as a special case in [14, Lemma 9]:

Lemma A

For any \(A>0\), uniformly for \(2 \le k \le A\log \log x\), we have

where \(C(3,4)=\gamma +\sum _{p \in \mathbb {P}}\left( \log \left( 1-\frac{1}{p}\right) +\frac{2\lambda (p)}{p}\right) \), \(\gamma \) is the Euler-Mascheroni constant, \(\lambda (p)\) is the indicator function of primes in the residue class \(3 \bmod 4\) and

We will show that Lemma A with some extra work implies the following Corollary.

Corollary 1

Uniformly for \(\frac{\log \log x}{2}-1 \le k \le \frac{\log \log x}{2}+\sqrt{\frac{\log \log x}{2}}\) we have

Proof

In view of Lemma A and with \(k\sim \frac{\log \log x}{2}\) we see that it suffices to check that, independent of the choice of k and for sufficiently large x, there exists a constant \(c>0\) such that

Note that the left hand side of the above inequality is exactly the coefficient of the main term \(\frac{1}{2^k}\frac{x}{\log x}\frac{(\log _2x)^{k-1}}{(k-1)!}\) for k in the range given in the Corollary. The constant C(3, 4) does not depend on k. Using Mertens’ Formula (cf. [16, p. 19: Theorem 1.12]) in the form

we get

where M(3, 4) is the constant appearing in

which was studied by Languasco and Zaccagnini in [12].Footnote 1 The computational results of Languasco and Zaccagnini imply that \(0.0482<M(3,4)<0.0483\) and hence allow for the following lower bound for C(3, 4):

It remains to get a lower bound for \(h''\left( \frac{2(k-3)}{3 \log \log x}\right) \), where the function h is defined as in Lemma A. A straight forward calculation yields that

and

where

Note that for \(x \rightarrow \infty \) and \(\frac{\log \log x}{2}-1 \le k \le \frac{\log \log x}{2}+\sqrt{\frac{\log \log x}{2}}\) the term \(\frac{2(k-3)}{3 \log \log x}\) gets arbitrarily close to \(\frac{1}{3}\). Hence we may suppose that \(\frac{99}{300}\le \frac{2(k-3)}{3 \log \log x} \le \frac{101}{300}\) and it suffices to find a lower bound for \(h''(x)\) where \(\frac{99}{300}\le x \le \frac{101}{300}\). For x in this range Mathematica provides the following bounds on the Gamma function and its derivatives

Furthermore we have

Later we will use that

and

Finally, using \(\log (1+\frac{x}{p})\le \frac{x}{p}\), we get

Applying the explicit bounds calculated above, for \(\frac{99}{300} \le x \le \frac{101}{300}\) we obtain:

This implies for sufficiently large x:

Together with (4) this leads to an admissible choice of \(c=0.802\) in (3). \(\square \)

5 The counting function S(x)

Proof of Theorem

As in (1) we set

where the sets \(S_i\) are defined as in (2). The set S has Property P by Lemma 2 and it remains to work out a lower bound for the size of the counting function S(x). For sufficiently large x there exists a uniquely determined integer \(k \in \mathbb {N}\) such that \(e^{2e^{2k}} \le x < e^{2e^{2(k+1)}}\) hence

It depends on the size of x, which \(S_i\) makes the largest contribution. For a given x we take several sets \(S_{k+2},S_{k+3}, \ldots , S_{k+l}\), \(l = \lfloor \sqrt{\frac{\log _2 \sqrt{x}}{2}} \rfloor \), as the number of prime factors \(p \equiv 3 \bmod 4\) of a typical integer less than x is in

Using Corollary 1 as well as the fact that the i-th prime in the residue class \(3 \bmod 4\) is asymptotically of size \(2 i \log i\) for given \(2 \le j \le l\) we get

We deal with the fractions \(\mathrm {F}_1\) and \(\mathrm {F}_2\) on the right hand side of (6) separately. With the given range of j and (5) we have that

It remains to deal with \(\mathrm {F}_2\). Using the given range of k and j we have that \(k+j \le \log _2\sqrt{x}\) and, again for sufficiently large x, for the numerator of \(F_2\) we get

Here we used that

and that for \(0 \le y \le \frac{1}{2}\) we certainly have that \(\log (1-y) \ge -2y\). To deal with the denominator of \(\mathrm {F}_2\) we apply Stirling’s Formula and get

Altogether we get

Since

it suffices to check that for any \(x>0\) and for our choices of j there exists a fixed constant \(c>0\) such that

For \(j\ge 2\) we have that \(\left( 1+\frac{2(j-1)}{\log _2\sqrt{x}}\right) ^{1-j}\) is monotonically decreasing in j and get

Therefore for \(j \ge 2\) the constant c in (8) may be chosen as \(c=\frac{1}{e}\) for sufficiently large x. Together with (7) this implies

Altogether for the counting function of any of the sets \(S_i\) with \(\lfloor \frac{\log _2\sqrt{x}}{2}\rfloor +2 \le i \le \lfloor \frac{\log _2\sqrt{x}}{2}\rfloor + \lfloor \sqrt{\frac{\log _2\sqrt{x}}{2}}\rfloor \) we have

Summing these contributions up we finally get

\(\square \)

Notes

Note that our constant M(3, 4) corresponds to the constant M(4, 3) in the work of Languasco and Zaccagnini.

References

Baier, S.: A note on P-sets. Integers 4(A13), 6 (2004)

Banks, W. D., Martin, G.: Optimal primitive sets with restricted primes. Integers 13, A69, 10 (2013)

Besicovitch, A.S.: On the density of certain sequences of integers. Math. Ann. 110(1), 336–341 (1935)

Erdős, P.: Note on Sequences of integers no one of which is divisible by any other. J. London Math. Soc. 10(1), 126–128 (1935)

Erdős, P.: On sequences of integers no one of which divides the product of two others and on some related problems. Mitt. Forsch.-Inst. Math. Mech. Univ. Tomsk 2, 74–82 (1938)

Erdős, P.: Some old and new problems on additive and combinatorial number theory. In: Combinatorial Mathematics: Proceedings of the Third International Conference (New York, 1985), Ann. New York Acad. Sci., vol. 555, pp. 181–186. New York Acad. Sci., New York (1989)

Erdős, P.: Some of my favourite unsolved problems. Math. Japon. 46(3), 527–538 (1997)

Erdős, P.: Some of my new and almost new problems and results in combinatorial number theory. In: Number theory (Eger, 1996), pp. 169–180. de Gruyter, Berlin (1998)

Erdős, P., Sárközi, A.: On the divisibility properties of sequences of integers. Proc. London Math. Soc. 21, 97–101 (1970)

Halberstam, H., Roth, K.F.: Sequences, 2nd edn. Springer-Verlag, New York-Berlin (1983)

Landau, E.: Sur quelques problèmes relatifs à la distribution des nombres premiers. Bull. Soc. Math. France 28, 25–38 (1900)

Languasco, A., Zaccagnini, A.: Computing the Mertens and Meissel-Mertens constants for sums over arithmetic progressions. Experiment. Math. 19(3), 279–284 (2010). With an appendix by Karl K. Norton, computational results available online: http://www.math.unipd.it/~languasc/Mertenscomput/Mqa/Msumfinalresults.pdf (URL last checked: 08.08.2016)

Martin, G., Pomerance, C.: Primitive sets with large counting functions. Publ. Math. Debrecen 79(3–4), 521–530 (2011)

Meng, X.: Large bias for integers with prime factors in arithmetic progressions. ArXiv e-prints, available at 1607.01882 (2016)

Schoen, T.: On a problem of Erdős and Sárközy. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 94(1), 191–195 (2001)

Tenenbaum, G.: Introduction to analytic and probabilistic number theory, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, vol. 163, third edn. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI (2015)

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Graz University of Technology. Parts of this research work were done when the first author was visiting the FIM at ETH Zürich, and the second author was visiting the Institut Élie Cartan de Lorraine of the University of Lorraine. The authors thank these institutions for their hospitality. The authors are also grateful to the referee for suggestions on the manuscript and would like to thank Xianchang Meng for some discussion on his recent paper [14].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by J. Schoißengeier.

The authors are supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): W1230, Doctoral Program ‘Discrete Mathematics’.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Elsholtz, C., Planitzer, S. On Erdős and Sárközy’s sequences with Property P. Monatsh Math 182, 565–575 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00605-016-0995-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00605-016-0995-9

Keywords

- Sequences with Property P

- Sums of two squares

- Primes in arithmetic progressions

- Distribution of integers with given prime factorization